TAKING PHOTOS IN FOG, MIST OR HAZE

Photography in fog, mist or haze can give a wonderfully moody and atmospheric feel to your subjects. However, it's also very easy to end up with photos that look washed-out and flat. This techniques article uses examples to illustrate how to make the most out of photos in these unique shooting environments.

Clare Bridge in the fog at night (version 1) - Cambridge, UK

OVERVIEW

Fog usually forms in the mid to late evening, and often lasts until early the next morning. It is also much more likely to form near the surface of water that is slightly warmer than the surrounding air. In this techniques article, we'll primarily talk about fog, but the photographic concepts apply similarly to mist or haze.

Photographing in the fog is very different from the more familiar photography in clear weather. Scenes are no longer necessarily clear and defined, and they are often deprived of contrast and color saturation:

Examples of photos which appear washed-out and de-saturated due to the fog.

Both photos are from St John's College, Cambridge, UK.

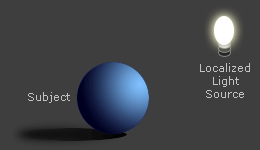

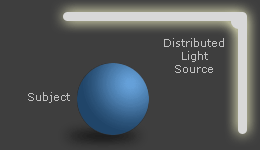

In essence, fog is a natural soft box: it scatters light sources so that their light originates from a much broader area. Compared to a street lamp or light from the sun on a clear day, this dramatically reduces contrast:

A Lamp or the Sun on a Clear Day

A Lamp or the Sun on a Clear Day(High Contrast)

Light in the Fog, Haze or Mist

Light in the Fog, Haze or Mist (Low Contrast)

Scenes in the fog are also much more dimly lit — often requiring longer exposure times than would otherwise be necessary. In addition, fog makes the air much more reflective to light, which often tricks your camera's light meter into thinking that it needs to decrease the exposure. Just as with photographs in the snow, fog therefore usually requires dialing in some positive exposure compensation.

In exchange for all of these potential disadvantages, fog can be a powerful and valuable tool for emphasizing the depth, lighting, and shape of your subjects. As you will see later, these traits can even make scenes feel mysterious and uniquely moody — an often elusive, but well sought after prize for photographers. The trick is knowing how to make use of these unique assets — without also having them detract from your subject.

EMPHASIZING DEPTH

Mathematical Bridge in Queens' College, Cambridge.

As objects become progressively farther from your camera, not only do they become smaller, but they also lose contrast — and sometimes quite dramatically. This can be both a blessing and a curse, because while it exaggerates the difference between near and far objects, it also makes distant objects difficult to photograph in isolation.

In the example to the left, there are at least four layers of trees which cascade back towards the distant bridge. Notice how both color saturation and contrast drop dramatically with each successively distant tree layer. The furthest layer, near the bridge, is reduced to nothing more than a silhouette, whereas the closest layer has near full color and contrast.

Southwest coast of Sardinia in haze.

Although there are no steadfast rules with photographing in the fog, it's often helpful to have at least some of your subject close to the camera. This way a portion of your image can contain high contrast and color, while also hinting at what everything else would look like otherwise. This also serves to add some tonal diversity to the scene.

EMPHASIZING LIGHT

View of King's College Bridge

from Queens' College, Cambridge, UK.

Water droplets in the fog or mist make light scatter a lot more than it would otherwise. This greatly softens light, but also makes light streaks visible from concentrated or directional light sources. The classic example is the photo in a forest with early morning light: when the photo is taken in the direction of this light, rays of light streak down from the trees and scatter off of this heavy morning air.

In the example to the right, light streaks are clearly visible from an open window and near the bridge, where a large tree partially obstructs an orange lamp. However, when the camera was moved just a few feet backwards, the streaks from the window were no longer visible.

Spires above entrance to King's College, Cambridge

during BBC lighting of King's Chapel for the boy's choir.

The trick to making light rays stand out is to carefully plan your vantage point. Light rays will be most apparent if you are located close to (but not at) where you can see the light source directly. This "off-angle" perspective ensures that the scattered light will both be bright and well-separated from the darker looking air.

On the other hand, if the fog is very dense or the light source is extremely concentrated, then the light rays will be clearly visible no matter what vantage point you have. The second example above was taken in air that was otherwise not visibly foggy, but the light sources were extremely intense and concentrated. Additionally, the scattered light was much brighter relative to the sky because it was taken after sunset.

SHAPES & SILHOUETTES

Swan at night on the River Cam, Cambridge.

Fog can emphasize the shape of subjects because it downplays their internal texture and contrast. Often, the subject can even be reduced to nothing more than a simple silhouette.

In the photo to the left, the swan's outline has been greatly exaggerated because the low-laying fog has washed out nearly all remains of the wall behind the swan. Furthermore, the bright fog background contrasts prominently with the relatively darker swan.

Rear gate entrance to Trinity

College, Cambridge, UK.

Just make sure to expose based on the fog — and not the subject — if you want this subject to appear as a dark silhouette. Alternatively, you could dial in a negative exposure compensation to make sure that objects do not turn out too bright. You will of course also need to pay careful attention to the relative position of objects in your scene, otherwise one object's outline or border may overlap with another object.

In the example to the right, the closest object — a cast iron gate — stands out much more than it would otherwise against this tangled backdrop of tree limbs. Behind this gate, each tree silhouette is visible in layers because the branches become progressively fainter the farther they are in the distance.

PHOTOGRAPHING FROM WITHOUT

You've perhaps heard of the saying: "it's difficult to photograph a forest from within." This is because it can be hard to get a sense of scale by photographing just a cluster of trees — you have to go outside the forest so you can see its boundaries, and not have individual trees hamper this perspective. The very same technique can often be very helpful with fog or haze.

left: Mt Rainier breaking through the clouds - Washington, USA

right: sunset above the haze on Mt Wilson - Los Angeles, California, USA

This way you can capture the unique atmospheric effects of fog or haze, but without also incurring its contrast-reducing disadvantages (at least for objects outside the fog/haze). In the case of fog, from a distance it's really nothing more than low-laying clouds.

TIMING THE FOG FOR MAXIMAL IMPACT

Just as with weather and clouds, timing when to take a photo in the fog can also make a big difference with how the light appears. Depending on the type of fog, it can move in clumps and vary in thickness with time. However, these differences are sometimes difficult to spot if they happen slowly, since our eyes adjust to the changing contrast. Try moving your mouse over the labels below to see how the scene changed over just 6 minutes:

|

||

| First Photograph | +2 minutes | +6 minutes |

Another important consideration is the apparent texture of fog. Even if you time the photograph for when you feel there's the most interesting distribution of fog, this fog may not retain its texture if the exposure time is not short enough. In general, the shutter speed needs to be a second or less in order to prevent the fog's texture from smoothing out. However, you might be able to get away with longer exposures when the fog is moving more slowly, or when your subject is not magnified by as much. Move your mouse over the image below to see how the exposure time affects the appearance of mist above the water:

|

|

| Shorter Exposure (1 second) |

Longer Exposure (30 seconds) |

Clare Bridge in low-laying fog at night (version 2) - Cambridge, UK

Note that the above image is the very same bridge that was shown as the first image in this article. Fog can dramatically change the appearance of a subject depending on where it is located, and how dense it is in that location.

Although the shorter exposure does a much better job of freezing the fog's motion , it also has a substantial impact on the amount of image noise when viewed at 100%. This can be a common problem with fog photography, since (i) fog is most likely to occur in the late evening through to the early morning (when light is low) and (ii) fog greatly reduces the amount of light reaching your camera after reflecting off the subject. Sometimes freezing the motion of fog therefore isn't an option if you want to avoid noise.

BEWARE OF CONDENSATION

If water droplets are condensing out of the air, then you can be assured that these same droplets are also likely to condense on the surface of your lens or inside your camera. If your camera is at a similar temperature to the air, and the fog isn't too dense, then you may not notice any condensation at all. On the other hand, expect substantial condensation if you previously had your camera indoors, and it is warmer outside.

Fortunately, there's an easy way to minimize condensation caused by going from indoors to outdoors. Before taking your camera and lens into a warmer humid environment, place all items within a plastic bag and ensure it is sealed airtight. You can then take these sealed bags outdoors, but you have to wait until everything within the bags have have reached the same temperature as outdoors before you open the bags. For large camera lenses with many elements, this can take 30 minutes or more if the indoor-outdoor temperature difference is big.

Unfortunately, sometimes a little condensation is unavoidable. Just make sure to bring a lens cloth with you for repeatedly wiping the front of your lens.