UNDERSTANDING GAMMA CORRECTION

Gamma is an important but seldom understood characteristic of virtually all digital imaging systems. It defines the relationship between a pixel's numerical value and its actual luminance. Without gamma, shades captured by digital cameras wouldn't appear as they did to our eyes (on a standard monitor). It's also referred to as gamma correction, gamma encoding or gamma compression, but these all refer to a similar concept. Understanding how gamma works can improve one's exposure technique, in addition to helping one make the most of image editing.

WHY GAMMA IS USEFUL

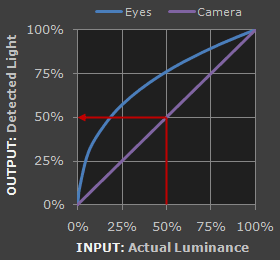

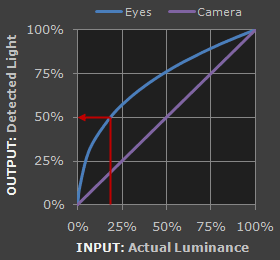

1. Our eyes do not perceive light the way cameras do. With a digital camera, when twice the number of photons hit the sensor, it receives twice the signal (a "linear" relationship). Pretty logical, right? That's not how our eyes work. Instead, we perceive twice the light as being only a fraction brighter — and increasingly so for higher light intensities (a "nonlinear" relationship).

Reference Tone

Reference Tone

Select:

Select:

| Perceived as 50% as Bright by Our Eyes |

| Detected as 50% as Bright by the Camera |

Refer to the tutorial on the photoshop curves tool if you're having trouble interpreting the graph.

Accuracy of comparison depends on having a well-calibrated monitor set to a display gamma of 2.2.

Actual perception will depend on viewing conditions, and may be affected by other nearby tones.

For extremely dim scenes, such as under starlight, our eyes begin to see linearly like cameras do.

Compared to a camera, we are much more sensitive to changes in dark tones than we are to similar changes in bright tones. There's a biological reason for this peculiarity: it enables our vision to operate over a broader range of luminance. Otherwise the typical range in brightness we encounter outdoors would be too overwhelming.

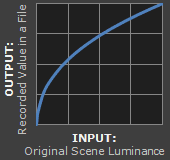

But how does all of this relate to gamma? In this case, gamma is what translates between our eye's light sensitivity and that of the camera. When a digital image is saved, it's therefore "gamma encoded" — so that twice the value in a file more closely corresponds to what we would perceive as being twice as bright.

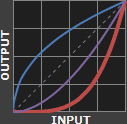

Technical Note: Gamma is defined by Vout = Vingamma , where Vout is the output luminance value and Vin is the input/actual luminance value. This formula causes the blue line above to curve. When gamma<1, the line arches upward, whereas the opposite occurs with gamma>1.

2. Gamma encoded images store tones more efficiently. Since gamma encoding redistributes tonal levels closer to how our eyes perceive them, fewer bits are needed to describe a given tonal range. Otherwise, an excess of bits would be devoted to describe the brighter tones (where the camera is relatively more sensitive), and a shortage of bits would be left to describe the darker tones (where the camera is relatively less sensitive):

Note: Above gamma encoded gradient shown using a standard value of 1/2.2

See the tutorial on bit depth for a background on the relationship between levels and bits.

Notice how the linear encoding uses insufficient levels to describe the dark tones — even though this leads to an excess of levels to describe the bright tones. On the other hand, the gamma encoded gradient distributes the tones roughly evenly across the entire range ("perceptually uniform"). This also ensures that subsequent image editing, color and histograms are all based on natural, perceptually uniform tones.

However, real-world images typically have at least 256 levels (8 bits), which is enough to make tones appear smooth and continuous in a print. If linear encoding were used instead, 8X as many levels (11 bits) would've been required to avoid image posterization.

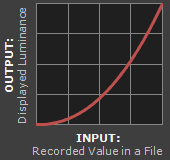

GAMMA WORKFLOW: ENCODING & CORRECTION

Despite all of these benefits, gamma encoding adds a layer of complexity to the whole process of recording and displaying images. The next step is where most people get confused, so take this part slowly. A gamma encoded image has to have "gamma correction" applied when it is viewed — which effectively converts it back into light from the original scene. In other words, the purpose of gamma encoding is for recording the image — not for displaying the image. Fortunately this second step (the "display gamma") is automatically performed by your monitor and video card. The following diagram illustrates how all of this fits together:

is Saved as a JPEG File

1. Image File Gamma

1. Image File Gamma

on a Computer Monitor

2. Display Gamma

2. Display Gamma

3. System Gamma

3. System Gamma

1. Depicts an image in the sRGB color space (which encodes using a gamma of approx. 1/2.2).

2. Depicts a display gamma equal to the standard of 2.2

1. Image Gamma. This is applied either by your camera or RAW development software whenever a captured image is converted into a standard JPEG or TIFF file. It redistributes native camera tonal levels into ones which are more perceptually uniform, thereby making the most efficient use of a given bit depth.

2. Display Gamma. This refers to the net influence of your video card and display device, so it may in fact be comprised of several gammas. The main purpose of the display gamma is to compensate for a file's gamma — thereby ensuring that the image isn't unrealistically brightened when displayed on your screen. A higher display gamma results in a darker image with greater contrast.

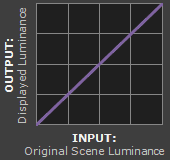

3. System Gamma. This represents the net effect of all gamma values that have been applied to an image, and is also referred to as the "viewing gamma." For faithful reproduction of a scene, this should ideally be close to a straight line (gamma = 1.0). A straight line ensures that the input (the original scene) is the same as the output (the light displayed on your screen or in a print). However, the system gamma is sometimes set slightly greater than 1.0 in order to improve contrast. This can help compensate for limitations due to the dynamic range of a display device, or due to non-ideal viewing conditions and image flare.

IMAGE FILE GAMMA

The precise image gamma is usually specified by a color profile that is embedded within the file. Most image files use an encoding gamma of 1/2.2 (such as those using sRGB and Adobe RGB 1998 color), but the big exception is with RAW files, which use a linear gamma. However, RAW image viewers typically show these presuming a standard encoding gamma of 1/2.2, since they would otherwise appear too dark:

Linear RAW Image

Linear RAW Image(image gamma = 1.0)

Gamma Encoded Image

Gamma Encoded Image(image gamma = 1/2.2)

If no color profile is embedded, then a standard gamma of 1/2.2 is usually assumed. Files without an embedded color profile typically include many PNG and GIF files, in addition to some JPEG images that were created using a "save for the web" setting.

Technical Note on Camera Gamma. Most digital cameras record light linearly, so their gamma is assumed to be 1.0, but near the extreme shadows and highlights this may not hold true. In that case, the file gamma may represent a combination of the encoding gamma and the camera's gamma. However, the camera's gamma is usually negligible by comparison. Camera manufacturers might also apply subtle tonal curves, which can also impact a file's gamma.

DISPLAY GAMMA

This is the gamma that you are controlling when you perform monitor calibration and adjust your contrast setting. Fortunately, the industry has converged on a standard display gamma of 2.2, so one doesn't need to worry about the pros/cons of different values. Older macintosh computers used a display gamma of 1.8, which made non-mac images appear brighter relative to a typical PC, but this is no longer the case.

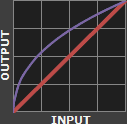

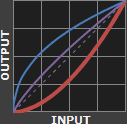

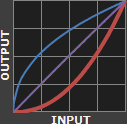

Recall that the display gamma compensates for the image file's gamma, and that the net result of this compensation is the system/overall gamma. For a standard gamma encoded image file (—), changing the display gamma (—) will therefore have the following overall impact (—) on an image:

Display Gamma 1.0

Display Gamma 1.0

Display Gamma 1.8

Display Gamma 1.8

Display Gamma 2.2

Display Gamma 2.2

Display Gamma 4.0

Display Gamma 4.0

Diagrams assume that your display has been calibrated to a standard gamma of 2.2.

Recall from before that the image file gamma (—) plus the display gamma (—) equals the overall system gamma (—). Also note how higher gamma values cause the red curve to bend downward.

If you're having trouble following the above charts, don't despair! It's a good idea to first have an understanding of how tonal curves impact image brightness and contrast. Otherwise you can just look at the portrait images for a qualitative understanding.

How to interpret the charts. The first picture (far left) gets brightened substantially because the image gamma (—) is uncorrected by the display gamma (—), resulting in an overall system gamma (—) that curves upward. In the second picture, the display gamma doesn't fully correct for the image file gamma, resulting in an overall system gamma that still curves upward a little (and therefore still brightens the image slightly). In the third picture, the display gamma exactly corrects the image gamma, resulting in an overall linear system gamma. Finally, in the fourth picture the display gamma over-compensates for the image gamma, resulting in an overall system gamma that curves downward (thereby darkening the image).

The overall display gamma is actually comprised of (i) the native monitor/LCD gamma and (ii) any gamma corrections applied within the display itself or by the video card. However, the effect of each is highly dependent on the type of display device.

CRT Monitors

CRT Monitors

LCD (Flat Panel) Monitors

LCD (Flat Panel) Monitors

CRT Monitors. Due to an odd bit of engineering luck, the native gamma of a CRT is 2.5 — almost the inverse of our eyes. Values from a gamma-encoded file could therefore be sent straight to the screen and they would automatically be corrected and appear nearly OK. However, a small gamma correction of ~1/1.1 needs to be applied to achieve an overall display gamma of 2.2. This is usually already set by the manufacturer's default settings, but can also be set during monitor calibration.

LCD Monitors. LCD monitors weren't so fortunate; ensuring an overall display gamma of 2.2 often requires substantial corrections, and they are also much less consistent than CRT's. LCDs therefore require something called a look-up table (LUT) in order to ensure that input values are depicted using the intended display gamma (amongst other things). See the tutorial on monitor calibration: look-up tables for more on this topic.

Technical Note: The display gamma can be a little confusing because this term is often used interchangeably with gamma correction, since it corrects for the file gamma. However, the values given for each are not always equivalent. Gamma correction is sometimes specified in terms of the encoding gamma that it aims to compensate for — not the actual gamma that is applied. For example, the actual gamma applied with a "gamma correction of 1.5" is often equal to 1/1.5, since a gamma of 1/1.5 cancels a gamma of 1.5 (1.5 * 1/1.5 = 1.0). A higher gamma correction value might therefore brighten the image (the opposite of a higher display gamma).

OTHER NOTES & FURTHER READING

Other important points and clarifications are listed below.

- Dynamic Range. In addition to ensuring the efficient use of image data, gamma encoding also actually increases the recordable dynamic range for a given bit depth. Gamma can sometimes also help a display/printer manage its limited dynamic range (compared to the original scene) by improving image contrast.

- Gamma Correction. The term "gamma correction" is really just a catch-all phrase for when gamma is applied to offset some other earlier gamma. One should therefore probably avoid using this term if the specific gamma type can be referred to instead.

- Gamma Compression & Expansion. These terms refer to situations where the gamma being applied is less than or greater than one, respectively. A file gamma could therefore be considered gamma compression, whereas a display gamma could be considered gamma expansion.

- Applicability. Strictly speaking, gamma refers to a tonal curve which follows a simple power law (where Vout = Vingamma), but it's often used to describe other tonal curves. For example, the sRGB color space is actually linear at very low luminosity, but then follows a curve at higher luminosity values. Neither the curve nor the linear region follow a standard gamma power law, but the overall gamma is approximated as 2.2.

- Is Gamma Required? No, linear gamma (RAW) images would still appear as our eyes saw them — but only if these images were shown on a linear gamma display. However, this would negate gamma's ability to efficiently record tonal levels.

For more on this topic, also visit the following tutorials:

- Digital Exposure Techniques: Expose to the Right, Clipping & Noise

Learn why gamma and linear RAW files influence a photo's optimal exposure. - How to Calibrate Your Monitor Calibration for Photography

Learn how to accurately set your computer's display gamma.