Results 41 to 60 of 85

-

22nd April 2021, 04:51 AM #41

-

22nd April 2021, 12:33 PM #42

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

- Location

- Texas

- Posts

- 6,956

- Real Name

- Ted

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

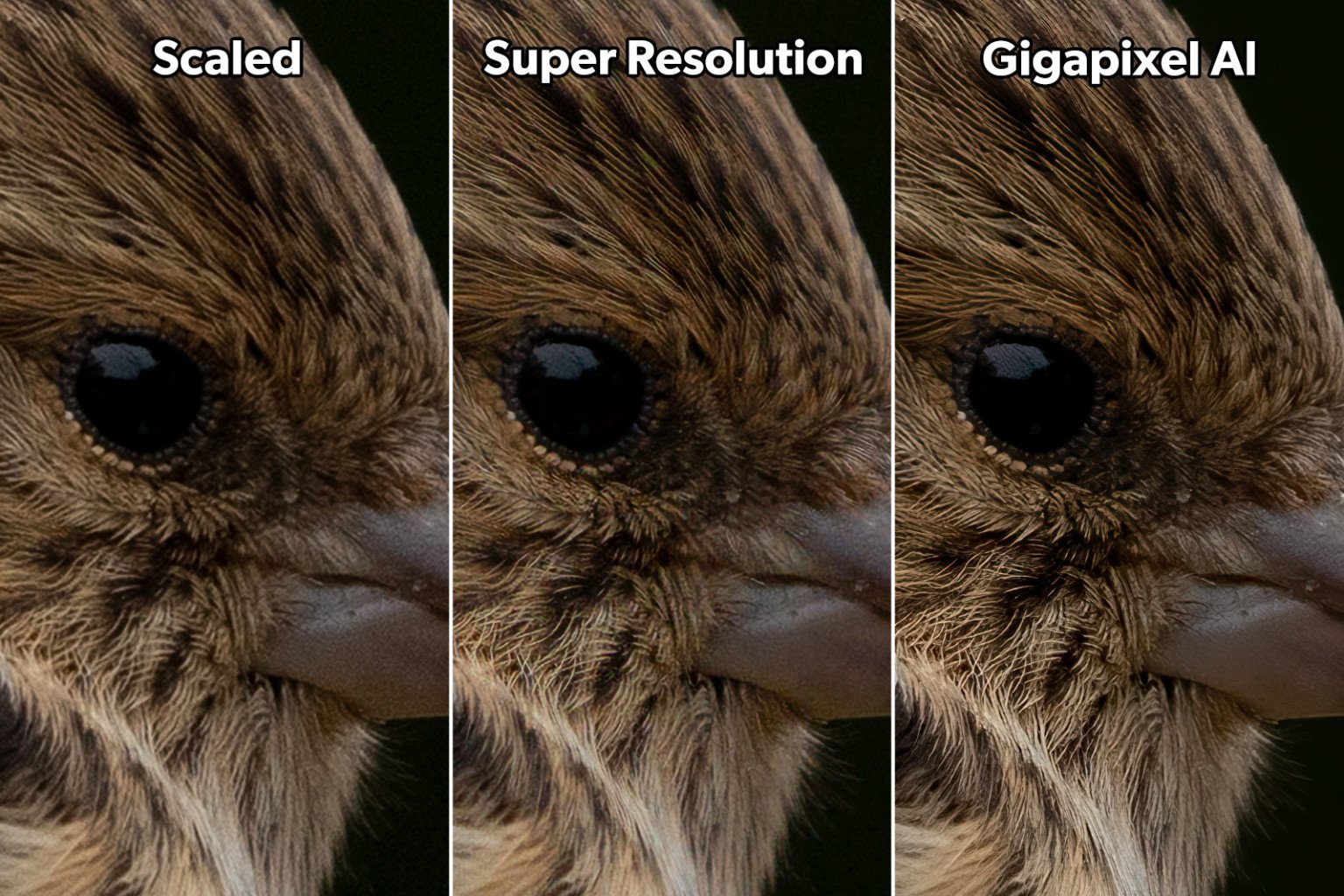

I take it that you've already considered or tried Gigapixel AI or Photoshop Super Resolution instead of splurging on more MP, Dan?

https://petapixel.com/2021/03/25/pet...-gigapixel-ai/

.

-

22nd April 2021, 12:44 PM #43

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

I've tried both, and I will continue to use the Adobe function sometimes, as I own the software. I tried only a demo of Gigapixel AI and decided it wasn't worth adding yet more software. I've found that under some circumstances, Super Resolution can be a big help. However, it isn't re-creating data that you failed to capture. Rather, it's guessing, based on some large training set, what data you didn't capture. It's just a very powerful imputation procedure. I'm not confident yet that it will work more consistently than other machine-learning-based functions, which often work well if the image happens to be similar to those in the training set. Once the world has more experience with that particular function, I may change my thinking.

As a good example of this, the "select subject" function in photoshop is also ML-based. In some cases, it works extremely well; it's almost unnerving how well it finds the subject. In other cases, it simply fails.

For that matter, many of the current resizing options, which use an entirely different approach to imputation, also work pretty well. However, when the uprezzing is extreme, I'm less willing to rely on them. Taking a 20 MP image, cropping by 50% or more--as is sometimes necessary--and then blowing it up to print 17 x 22 is a heavy lift. All that said, I've had only a few prints that suffered appreciably from uprezzing.

What would be really interesting (to me, anyway) would be a direct test of this, using no processing other than imputation, comparing an image with no imputation, an image with conventional resizing up that those same dimensions, and an image with Super Resoltion. That might be enough to allow me to sacrifice 1/3 of my current pixel count.

-

22nd April 2021, 12:58 PM #44

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

- Location

- Texas

- Posts

- 6,956

- Real Name

- Ted

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

There's good few of just such comparisons in the PetaPixel article, for example:

https://petapixel.com/assets/uploads...-1536x1024.jpg

Just crops, though ...

-

22nd April 2021, 04:49 PM #45

-

22nd April 2021, 07:23 PM #46

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

- Location

- Texas

- Posts

- 6,956

- Real Name

- Ted

-

22nd April 2021, 08:32 PM #47

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

This is actually quite interesting as a general discussion and my comments here do no apply to anyone in particular.

I have been doing some work for a course on the history of photography and towards the end of the 19th century we have the movement towards Pointillism: arguably a forerunner of the pixel, but in a painting context.

This was part of an artistic movement called Neo-Impressionsim (1885-1935): based, among other things, on the use of colour dots that, seen from a distance, expressed many other colours as our eyes blended the different proportions of differently coloured dots to create our own, brighter blended images.

To quote from arthistory.org: "Neo-Impressionism foregrounded the science of optics and color to forge a new and methodical technique of painting that eschewed the spontaneity and romanticism that many Impressionists celebrated. Relying on the viewer's capacity to optically blend the dots of color on the canvas, the Neo-Impressionists strove to create more luminous paintings that depicted modern life. With urban centers growing and technology advancing, the artists sought to capture people's changing relationship with the city and countryside. Many artists in the following years adopted the Neo-Impressionist technique of Pointillism, the application of tiny dots of pigment, which opened the door to further explorations of color and eventually abstract art."

For an example of this see: https://www.theartstory.org/artist/s...rtworks/#pnt_2

Basically, artists were applying the equivalent of pixels using tiny blobs of paint and we were meant to appreciate the result from a distance, thus allowing our eyes to absorb and blend the dots into different colours, tones and hues. If one moved close to the images they dissolved into dots again. Obviously, the artists was working up close and personal with the work, but the audience were not intended to do so, or the effect was lost - the equivalent of pixelation to us.

At the same time in the photographic world was Pictorialism (1885-1920's), the move to soft-focus images, manipulated in post processing to include scratches, over-painting and blending of negatives to make photos look more "painterly" was in its heyday as photographers sought to have their images recognized as fine art. Photography had an identity crisis since the first images were created, especially the Daguerreotypes that were the first commercially viable photographs. They included both a positive and negative image on a metal plate, so that the image changed depending upon the angle at which it was viewed. That, combined with the fact that the pioneers were generally technical nerds and images were initially taken only of inanimate objects because of the excessively slow exposure times, meant that the conventional art community regarded photographs as technical miracles, but not art! This may also have been due to a fear that photography would destroy their livelihoods.

Desperate to overcome this attitude, Pictorialists often printed only one image and might destroy the negative to reinforce the uniqueness of the image and the "hand of Man" as an artist in the resultant work. In the US Alfred Steiglitz founded the Photo Succession movement which promoted this vision until he recanted in the second decade of the 20th Century. Later, the Group F:64 (among whom were Ansel Adams and Imogen Cunningham) took this even further, using an ethos of images that were taken with large-format cameras, at extremely narrow apertures, and had no cropping. They certainly were happy to engage in serious PP to get their effects though.

The principle of examining images in extreme magnification extended to apply to the selection of negatives initially, particularly 35mm, but became a tool for looking at transparencies when they became available, and of course, now that we have very high-resolution monitors that can be taken to ever-higher levels of magnification. The question is: who is the end user and how will they view the result?

This history is in itself interesting, but it reinforces that there are always diverse and sometimes conflicting movements within any art movement - the technology might change, but the human element of diversity remains the same.Last edited by Tronhard; 22nd April 2021 at 08:43 PM.

-

22nd April 2021, 09:12 PM #48

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

- Location

- Texas

- Posts

- 6,956

- Real Name

- Ted

-

22nd April 2021, 09:43 PM #49

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

More or less. The question pertained to prints that require much more than 20 MPX at the printer's native resolution. The question is whether shooting with a 20 MP camera and relying on Super Resolution would be a substitute for having 50% more pixels (or more than 50%).

-

22nd April 2021, 10:23 PM #50

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

If you want to go historical, don't overlook the early adopters of the collodion process ...

-

22nd April 2021, 10:25 PM #51

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

The effect between a projected colour and mixing pigments was absolutely different. If one physically mixed RGB paints together, one got a subtractive mixing, giving at best a dark brown gunk! Mixing the RGB light of course give one white light. By placing colour dots close together the paint pigments stayed separate but our eyes mixed the colours in an additive process.

See an excellent YouTube documentary by Waldamar: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axf0AfL4ftI on this subject.

What gets me is that Seurat's paintings were often HUGE! It must have taken forever for him to create them and to get the very technical combinations of dots to get the mixed colours correct.Last edited by Tronhard; 22nd April 2021 at 10:33 PM.

-

22nd April 2021, 10:27 PM #52

-

22nd April 2021, 10:28 PM #53

-

22nd April 2021, 11:41 PM #54

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

- Location

- Texas

- Posts

- 6,956

- Real Name

- Ted

-

22nd April 2021, 11:58 PM #55

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

The question in my mind isnít the specific multiplier. Itís the extent to which imputed pixels can effectively substitute for real (data) pixels.

Sent from my iPad using Tapatalk

-

23rd April 2021, 03:04 PM #56

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

I don't think so. I think it is more a matter of terminology.

I'm using the terminology that is most common in statistics, at least around here. A "derived variable" is a variable that has been created from one or more variables that have values present in the data. That's what rendering a raw file is. One has a number of simple RGB values for each photosite (i.e., data that are present in the original file), and these have to be manipulated to render an image.

In contrast, imputed variables are variables inserted where there were no data initially, that is, where data were simply missing entirely. That's what Super Resolution does: it tries to figure out what data would have been there if the image had contained more data.

Uprezzzing also necessarily involves imputation. if the input is a file with 10 MP and the output is a file with 20 MP, the software has to generate values to plug in where none were present before.

Super Resolution is a fundamentally different method for figuring out what data to make up from whole cloth, but that's still what it's doing.

-

23rd April 2021, 11:00 PM #57

- Join Date

- Feb 2012

- Location

- Texas

- Posts

- 6,956

- Real Name

- Ted

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

An interesting line of thought. It seems to exclude the idea of viewing output at a "proper" distance and is more appropriate to those who step up to a large print with a jeweler's loupe at the ready.

On the other hand, I can double the width of an image using Nearest Neighbor then double the viewing distance and see no difference at all ...

-

24th April 2021, 08:51 PM #58

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

People take photos for a VERY wide range of purposes and have many perspectives on how they want an image to be viewed, or even what is "acceptable quality". I say this specifically so that I am seen to recognize that very large, finely detailed and precise images, absolutely have their place.

That said, the question needs to be asked: how are the mass of people (photographers and viewers) likely to practically view an image? In Dan's case, he seems to be creating images that he can view at a very detailed level close up and that creates a work that gives him (and assumedly his audience) satisfaction - and for that constituency that is absolutely fine - no argument there...

However, I would venture that the mass of viewers will not be so rigorous: they are likely to view an image from some distance to get the whole into their normal field of view, and that depends on the size and method of presentation. For prints there will be variations based on the printing technology and methodology as well as mounting. There is an increasing and massive population that will never look at a print at all - they will see them via a digital device or presented via web pages, and in many cases those are degraded according to the requirements of the service provider or page master.

Some time ago I read a book about a famous photo editor and he was writing about early, large-scale images, printed from film or early digital originals. Initially, image were relatively crude, both in capture and delivery; yet people were happy because they had never been exposed to such visuals before and of course knew no better.

In that context this article in DPREVIEW provides some context as to how we view such "primitive" images, as do the comments themselves: https://www.dpreview.com/news/331288...-for-nearly-2m

As he commented, while the quality of digital sources since then has massively increased, the need for their levels of display was somewhat redundant for the type of work that he saw. In this case, he was discussing the publishing and advertising industries: daily papers, periodicals and even high-end magazines downsized the images they got because that level of capture was far in excess of what was needed or practical for them to handle. It took up too many hours and resources, and readers didn't notice the difference. He also commented that the larger the image, naturally the further away people viewed. So while one might get to nose distance from a billboard and complain about the resolution, the mass of people would never do that and were quite happy with the images they saw at a "natural" distance. He ventured that even for fine art prints, there are limits to what the human eye will perceive, so very few people would actually get to pixel-peeping a print, consequently it was more a need for precision for the artist than the audience.

So, to sum up: as I started - we all take photos for different purposes and consequently there can never be an absolute one-size-sits-all solution to what gear we want to use or how we apply it. Still, I think I see some echoes of the situation of my previous post #47 regarding how and why people looked at paintings close up, or did not...Last edited by Tronhard; 24th April 2021 at 09:04 PM.

-

24th April 2021, 09:05 PM #59

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

Indeed, and I may be like a dog chasing my own tail.

Here's an example of an image where fine detail is important:

I've successfully printed this at 17 x 22 from an image taken with a 5D III, which is a 22.3 MP sensor. That would seem to undercut my argument that I benefit from 30 MP or so. But on the other hand, this is a studio image, so there was very little cropping, and hence little need to interpolate.

Now if someone will just give me an R6, I promise to take several comparison images with that and my 5D IV and compare large prints.

-

24th April 2021, 09:46 PM #60

Re: Things looking less good for DSLRs?

Hi Dan:

Gorgeous image and I'm sure the print is beautiful to view. I also looked at your webpage and was very impressed by your images - they are, indeed, beautiful and deserve respect for their quality. I think Monet would have liked your homage to his last and largest work!

As I said (several times) I see no lack of justification for you wanting to have more resolution in your images - if you were going to go for one of the currently generation of Canon MILCs, then maybe the R5, at 45MP, would perhaps be better for you. Surely your favourite camera vendor could let you borrow and R6 and R5, or you could even rent them if you want to check them out. Sadly, I think sending you my R6's from NZ might be a bit impractical! The important thing is what gives YOU, the creator, the joy and satisfaction of taking, processing and sharing your images via your chosen medium. That can have no argument.

The important thing is what gives YOU, the creator, the joy and satisfaction of taking, processing and sharing your images via your chosen medium. That can have no argument.

My general comment is more in the context of the general population and I would be interested in your perspective on that though, especially given the title of the thread.Last edited by Tronhard; 24th April 2021 at 09:52 PM.

Helpful Posts:

Helpful Posts:

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote